Deprescribing psychotropic medicines for behaviours that challenge ... - BMC Psychiatry

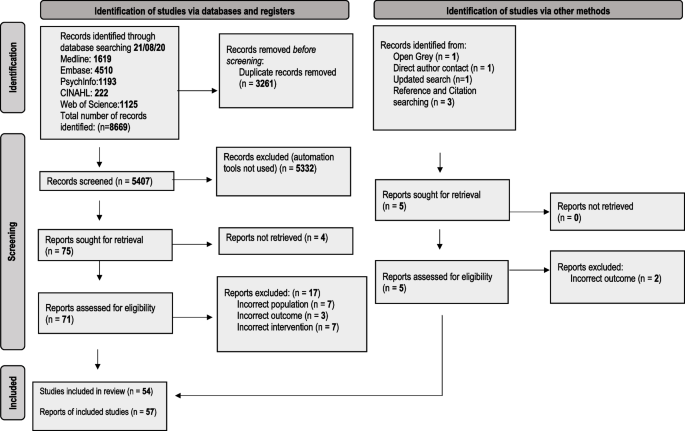

We identified 8675 records, and 57 reports relating to 54 studies met our eligibility criteria and were included in the review. This is reported in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the deprescribing of psychotropic medicines in people with intellectual disabilities prescribed for behaviour that challenges: a systematic review [19]

Studies excluded at full text review together with reasons were recorded and listed in Table 3. Summary tables of extracted data for included studies are reported in Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7. A summary table of quality appraisal for included studies is reported in Table 8.

Included studies were carried out in nine countries, in both inpatient (n = 31) and community settings (n = 24). One study did not report setting.

Details of participant characteristics and numbers were incompletely reported in several studies, and in studies conducted by the same researchers, there was lack of clarity regarding duplication of participants [34, 37, 77].The total number of participants across all studies where reported was 3292. The percentage of participants reported to have severe/profound intellectual disabilities varied across study types ranging from 49% for RCTs, 62% for non-randomised controlled studies and 72% for pre post studies without randomisation control. One case study reported the participant to have severe/profound intellectual disabilities. Furthermore, the level of intellectual disability was incompletely or not reported in 33% of studies and the amount and type of support provided to participants was not reported in any of the studies. Ethnicity was reported in only five studies.

The most frequently deprescribed psychotropic medicines across all studies were typical and atypical antipsychotics. Aside from one RCT, the prescribing and administration of pro re nata (PRN) medication for the management of behaviours that challenge was incompletely reported [31].

Intervention approaches ranged from sudden discontinuation to gradually tapering dosage over 28 weeks. Sixteen studies reported the deprescribing intervention as integral to or supported by the wider multidisciplinary team [37, 38, 44, 46,47,48,49,50,51, 54, 55, 57, 65, 66, 75]. However, there were no data reported regarding working across organisation boundaries such as between primary and secondary care and no data reporting specific non pharmacological interventions to support deprescribing although for three studies the deprescribing interventions were in the context of a Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) framework [37, 38, 75]. Evidence of pharmacists working within the multidisciplinary team (MDT) was reported in 11 studies [37, 38, 44, 47, 49, 51, 54, 57, 60, 65, 75] and pharmacist non-medical prescribers delivering the interventions were reported in three studies, although the same pharmacist prescriber was involved in all three [37, 38, 75]. Follow up ranged from immediately after medication was reduced or discontinued to 15 years. For 22 studies, follow up was variable or not specified. Outcomes were measured using a range of standardised rating tools and questionnaires. Input from patients, carers, and family and models of co-production in developing multidisciplinary deprescribing interventions were not reported. The reporting of shared decision-making approaches involving patients, carers, and clinicians within deprescribing interventions were reported in three studies (all within a Positive Behavioural Support (PBS) framework) [37, 38, 75, 78]. Quality of Life outcomes were only reported in one pre post study [34] and one paper reporting three case studies [14].

Across all study types there was incomplete reporting of rates of complete psychotropic discontinuation, at least 50% psychotropic dose reduction, represcribing, behavioural changes and emergence of adverse effects. Where reported in RCTs using a tapering approach to deprescribing, rates of complete deprescribing ranged from 33 to 84% [20, 21, 23, 31, 32]. Relapse rates due to worsening of behaviour ranged from 62.5% to no worsening. In the non randomised group of studies, Gerrard et al. [37] reported up to 60% complete discontinuation with a further 50% achieving a 50% dose reduction with only one person requiring represcribing This contrasted to findings by Zuddas et al. [42] who reported that all three people who achieved discontinuation displayed behavioural deterioration requiring represcribing.

Randomised control trials (RCTs)

Seven RCTs evaluated the effects of deprescribing antipsychotic medicines [20, 21, 23, 30,31,32, 79], three on typical antipsychotics, three on atypical antipsychotics, and one on both types. Four studies were conducted in community settings [20, 23, 31, 32], two studies were carried out in an inpatient settings [30, 79] and one study included a mix of both [21]. Sample sizes ranged from 22 to 100 participants, with participant ages, where reported, ranging from 5 years to 78 years, with all 7 studies reporting outcomes for adults, 4 studies reporting outcomes for adolescents (ages 10--19 years [80]) and two studies reporting outcomes for children. The majority of participants were male ranging from 48 to 87% across RCTs. Length of follow up period varied from 4 weeks to 9 months following discontinuation or maximum dosage reduction. Primary outcome measures were firstly the changes in frequency and intensity of episodes of behaviours that challenge at follow up (we report follow up as time after planned complete discontinuation or maximum dosage reduction) and secondly, numbers of participants who reduced or stopped their antipsychotic medication.

Changes in behaviours that challenge

Assessment of the effects of deprescribing antipsychotics on behaviours that challenge was a primary outcome in all seven RCTs. Deprescribing antipsychotic medication was associated with a reduction in behaviours that challenge irrespective of whether the antipsychotic was tapered over 14 or 28 weeks in an RCT by de Kuijper et al. [23] This study involving 98 participants in community settings reported firstly that higher ratings of extrapyramidal and autonomic symptoms at baseline were associated with less improvement of behavioural symptoms after discontinuation; and secondly, higher baseline Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) scores were associated with an increased likelihood of incomplete discontinuation [23].

Authors of studies where antipsychotic doses were reduced over 6 months [31] or 4 months [21] reported no clinically important changes in participants' levels of aggression or behaviours that challenge at 9 months and 1 month respectively after planned discontinuation. Furthermore in a study by Ramerman et al. [32] study no change in irritability was reported when risperidone was reduced over 14 weeks in 86 participants compared to placebo.

In a study of the effects of withdrawal of zuclopentixol by Hassler et al. [79] behaviours that challenge increased at 12 weeks after sudden discontinuation of zuclopenthixol in 20 participants compared to the 19 participants that continued to be prescribed the antipsychotic. Heistad et al. [30] also reported increases in behaviours that challenge in participants undergoing deprescribing of thioridazine in a series of 5 separate groups within an RCT. Rates of relapse of behaviours that challenge were reported to be higher at 5 weeks follow up when risperidone was discontinued over 3 weeks in 38 adolescents and children in an RCT by the Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network research units [20]. Relapse rates were 62.5% for gradual placebo substitution and 12.5% for continued risperidone [20].

The deprescribing interventions of the three RCTs reporting overall increase in behaviours that challenge involved sudden discontinuation [30, 79] or tapering over the short time of 3 weeks. This compares to antipsychotics deprescribed over 14 to 28 weeks in studies reporting no change or a reduction in behaviours that challenge [21, 23, 31, 32]. In addition the follow up periods in the three RCTs [20, 30, 79] reporting increases in behaviours that challenge were shorter; 4 to 12 weeks compared to 4 weeks to 12 months in studies reporting no change or a reduction in behaviours that challenge [21, 23, 31, 32]. Two [30, 79] of the three RCTs reporting increases in behaviours that challenge were conducted in inpatient settings. Three [23, 31, 32] of the four studies reporting more favourable results regarding behaviours that challenge, were carried out in community settings, the fourth study [21] involving participants in both community and inpatient settings. The studies reporting less favourable effects on behaviours that challenges involved larger percentages of participants with severe or profound intellectual disabilities ranging from 34 to 72% [20, 30, 79]compared to 24 to 63% [23, 32] in two of the four studies reporting more favourable outcomes although two studies did not report level of intellectual disability [21, 31].

Reduction /discontinuation completion outcomes

Four studies [21, 23, 31, 32] used a study design involving tapering of the dose of antipsychotic dose three [21, 23, 32] of which reported numbers of participants achieving complete withdrawal.

Ahmed et al. [21] reported 33% of 36 participants achieved discontinuation with a further 19% achieving and maintaining at least a 50% reduction at one month follow up. de Kuijper et al. [23] reported 37% of 98 participants achieved complete discontinuation with significant improvements in behaviours that challenge at 12 weeks follow up. Secondly, they reported re-prescribing at follow up after an initially discontinuing in 7% of participants. Ramerman et al. [32] reported 82% of the 11 participants in the deprescribing group, completely withdrew from risperidone.

Other outcomes

Four studies reported outcomes of physical and mental health and wellbeing.

One study by de Kuijper et al. [24, 81] and another by Ramerman et al. [32] reported positive effects of deprescribing antipsychotics on physical health parameters. de Kuijpers et al. [24, 81] reported a mean decrease of 4 cm waist circumference, of 3.5 kg weight, 1.4 kg/m2 BMI, and 7.1 mmHg systolic blood pressure at 12 weeks follow up after planned discontinuation, in 98 participants following complete discontinuation of antipsychotics over 14 or 28 weeks. Ramerman et al. [32] reported favourable group time effects on weight, waist, body mass index, prolactin levels and testosterone levels in 11 participants who completely discontinued risperidone. However, this study was underpowered and follow up was limited to 8 weeks. Both complete discontinuation and dosage reduction of antipsychotics were reported by de Kuijper et al. [24] to lead to a decrease in prolactin plasma levels and an increase in levels of C- telopeptide type 1 collagen (CTX), the bone resorption marker [24]. Ahmed et al. [21] reported an association of typical antipsychotic reduction with increased dyskinesia. However the follow up time for this study was 4 weeks compared to the study by de Kuijper et al. [24]which had a follow up period of 12 weeks and the study by Ramerman et al. [32] which had an 8 week follow up period. Conversely, Hassler et al. [79] reported weight gain in participants who discontinued zuclopentixol [79] in an inpatient setting. Two [24, 32, 81] of the three studies reporting positive physical health outcomes were carried out in community settings and the third study [21] involved participants in both hospital and community settings.

Integrated synthesis of RCTs

The evidence from RCTs regarding the effects of deprescribing on behaviours that challenge at follow up was mixed. The length of follow up was inadequate for the majority of studies with four studies reporting follow up periods of between four and eight weeks [20,21,22, 30, 32] and a further two studies reporting follow up at 12 weeks [23, 24, 28, 79, 81] and therefore it could not be established if successful deprescribing could be maintained in those studies reporting positive effects or no change on behaviours that challenge.

The evidence suggests that discontinuing or reducing the dosage of antipsychotics can have positive effects on physical health such as the reversal of antipsychotic markers for metabolic syndrome. The several subclasses of antipsychotics and variable doses at baseline may limit the robustness of this evidence. Methodological limitations across all RCTs included the use of small sample sizes and limited reporting of information about blinding procedures and methods to ensure allocation concealment. Two studies did not make use of blinding [21, 23]. The treating physician was involved in the sampling and recruitment of participants in two RCTs leading to possible selection bias [21, 32].

Nonrandomised controlled studies

Seven nonrandomised controlled studies evaluated the effects of deprescribing antipsychotic medicines. Two studies were conducted in community settings [37, 42] and five studies were carried out in inpatient settings [35, 36, 39,40,41]. Sample sizes ranged from 6 to 80 participants, with participant ages, where reported, ranging from 7 years to 53 years, with 4 studies reporting outcomes for adults, one study reporting outcomes for adolescents (ages 10–19 years [80]) and one study reporting outcomes for children. The majority of participants were male ranging from 50 to 90% across studies. Length of follow up period varied from 8 weeks in one study to between 5 months and 12 months following discontinuation or maximum dosage reduction in those studies reporting. Two studies reported nonspecific variable follow up periods.

Behaviours that challenge

Two studies reported on changes in episodes or severity of behaviours that challenge. Zuddas et al. [42] reported progressive deterioration of behaviours in the 3 out of 10 adolescents and children participants who discontinued risperidone. A study by Swanson et al. [39] reported transient increases in ABC scores in 21 participants, 96% of whom had severe or profound intellectual disabilities, who discontinued risperidone and were co prescribed antiepileptic medication. However, this was not reported in the 19 participants who discontinued risperidone in the absence of antiepileptic medication.

Reduction /discontinuation outcomes

Two studies reported outcomes regarding numbers of participants who had their psychotropic medicines deprescribed. Zuddas et al. [42] reported that three children or adolescents discontinued risperidone although all three required the represcribing of an antipsychotic within 6 months following discontinuation.

A study by Gerrard et al. [37] comparing two groups of participants, reported a higher success rate for psychotropic medication reduction and discontinuation when this was carried out within a PBS framework. The authors reported that participants in the non-PBS group were more likely to have their medication increased following an initial reduction. Support was delivered by staff using a PBS framework for a minimum of three months post discontinuation or medication reduction. One patient required a medication increase or restart when supported by PBS. This compared to 66% of participants in the non-PBS group. However, evidence is limited by unequally matched groups in terms of intellectual disability [37] and the follow up times were variable.

Other outcomes

Four studies [35, 39,40,41] reported changes in dyskinesia scores following the deprescribing of antipsychotics. Aman and Singh [35] examined the effects of deprescribing typical antipsychotics on dyskinesias comparing a deprescribing group to a group that were not prescribed antipsychotics. The evidence was inconclusive although the deprescribing group was rated as having higher total dyskinesia scores.

Swanson et al. [39] reported transient increases in average Dyskinesia Identification System Condensed User Scale (DISCUS) scores after risperidone discontinuation with return to baseline 6 months after discontinuation. Wigal et al. [40] reported larger increases in DISCUS scores associated with greater dosage reductions of antipsychotics. Another study by the same authors measured the rates of dyskinesias during their medication review and dose reduction programme [41]. They reported that 63% of participants who discontinued antipsychotics and 29% of those who were receiving reduced dosages developed dyskinesias. In participants who were not medicated or where there was no change or increase in dosage, no dyskinesias were reported. All four studies were carried out in inpatient settings and most of the participants had severe or profound intellectual disabilities, ranging from 86 to 100%.

Pre post study designs

Twenty-seven pre-post studies evaluated the effects of deprescribing psychotropic medicines, with all studies reporting interventions involving antipsychotics and 6 studies reporting on interventions on more than one class of psychotropic medication [38, 46, 49,50,51, 55] including anxiolytics (n = 3), antidepressants (n = 4), sedatives/hypnotics (n = 2), benzodiazepines (n = 2), anticonvulsants (n = 1) and lithium (n = 2) in addition to antipsychotics [46, 49,50,51, 55, 77]. Eight studies were conducted in community settings,17 studies were carried out in inpatient settings, one study involved a mix of both, and one study did not report setting. Sample sizes ranged from 6 to 250 participants, with participant ages, where reported, ranging from 5 years to 84 years, with 14 studies reporting outcomes for adults, 6 studies reporting outcomes for adolescents (ages 10--19 years [80]) and one study reporting outcomes for children. The majority of participants were male ranging from 50 to 100% where reported. Length of follow up period varied from 8 weeks to 15 years following discontinuation or maximum dosage reduction with 12 studies reporting variable follow up or not reporting follow up periods.

Behaviours that challenge

From 12 studies reporting on the effects of deprescribing psychotropic medicines on behaviours that challenge the findings are mixed [33, 44, 46, 48, 52,53,54, 57,58,59, 61, 67]. Branford [44] reported no deterioration in behaviours that challenge in 25% of 123 participants who underwent a reduction of antipsychotics. However, 42% did show a deterioration in behaviours that challenge, and for 33%, changes in behaviour were not reported. de Kuijper et al. [33] reported at 16 weeks post planned discontinuation, 6% of participants had shown improvement and 9% had a worsening of behaviour; at 28 weeks, these percentages were 9 and 15%, and at 40 weeks 21 and 7%, respectively. They also concluded that at 28 weeks, those who had not achieved complete discontinuation had significantly more worsening of behaviour than those who had successfully discontinued. Ellenor et al. [46] reported ABS scores for 54 participants which showed a slight increase in behaviours that challenge for all three groups; medication reduced, medication stopped and control group. Fielding et al. [48] reported that all but eight of 68 participants whose antipsychotic medication was reduced, achieved permanent dosage reductions while maintaining rates of behaviours that challenge similar to those observed prior to deprescribing. They also found that behaviours that challenge decreased or remained stable for the majority although they slightly increased for some. In two studies by Janowsky et al. [52, 53] 40% of 138 participants with severe or profound intellectual disabilities and 96% of 49 participants with severe or profound intellectual disabilities were reported to experience a relapse in behaviours that challenge. Jauernig et al. [54] reported a lower frequency of behaviours that challenge at follow-up compared to baseline in all 3 patients (100%) whose antipsychotic had been discontinued and in 15 patients (79%) of 19 who underwent dose reduction. Luchins et al. [57] reported an improvement in behaviour associated with the reduction in prescribing of antipsychotics. Marholin et al. [58] reported reversible changes in behaviours that challenge when chlorpromazine was withdrawn suddenly and then restarted 23 days later in 6 participants with severe intellectual disabilities. Matthews and Weston [59]reported over 50% of 77 participants who were on regular thioridazine experienced behaviours that challenge during or following discontinuation. Adverse events were significantly associated with the duration of previous thioridazine prescription. May et al. [61] evaluated the effects of deprescribing risperidone in people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities and reported transient worsening of behaviours that challenge in 39%, persistent worsening in 39%, and progressive improvement in 22% of participants. Stevenson et al. [67] reported that 48.7% experienced onset or deterioration in behaviours or mental ill-health following the deprescribing of thioridazine.

Reduction /discontinuation outcomes

Nineteen studies [33, 38, 43, 44, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, 57, 60, 65,66,67] reported lower prescribing rates, complete discontinuation, or reduced dosages of psychotropic medicines,14 of which reported an evaluation of a clinical service involving multidisciplinary medication reviews with varying time periods for follow up [38, 44, 46,47,48,49,50,51, 54, 55, 57, 60, 65, 66]. Nine of the studies reported evaluations of medication reviews involving pharmacists [38, 44, 46, 47, 49, 51, 54, 60, 65]. A medication review programme by Branford [44] reported 16% of 198 adult participants withdrawn from antipsychotics and 28% maintained on reduced dosage of antipsychotics at 12 months follow up. One hundred and twenty-three of the 198 participants underwent a reduction of their antipsychotics and 25% discontinued antipsychotics while 46% were receiving reduced dosages at 12 months follow up. Gerrard et al. [38] reported that 24 psychotropic medications were stopped within their retrospective study; 20 of these were with PBS support and ongoing deprescribing continued at the time of publication of the study in 2020. de Kuijper et al. [33] reported 61% had completely discontinued antipsychotics at 16 weeks, 46% at 28 weeks, and 40% at 40 weeks. However, 32 % of participants who initially withdrew at 16 weeks were represcribed antipsychotics at 28 weeks follow up and 13% who withdrew at 28 weeks were represcribed antipsychotics at 40 weeks follow up. Studies by Findholt et al. [49] and Howerton et al. [50] reported a decrease in polypharmacy. A retrospective review by Luchins et al. [57] reported the reduction of antipsychotic prescribing was associated with prescribing other psychotropic medicines such as carbamazepine, lithium, and buspirone.

Other outcomes

Nine studies [34, 38, 45, 56, 62,63,64,65, 67] reported physical health and wellbeing findings, one of which also reported mental health and wellbeing outcomes. Ramerman et al. [34] reported improved physical health amongst those who completely discontinued antipsychotics, while social functioning and mental wellbeing initially deteriorated in those who incompletely discontinued; however, this was temporary, and they recovered at 6 months after planned discontinuation. In addition, they reported that participants who had completely discontinued had temporary decreases in mental wellbeing. Similar findings were reported by de Kuijper et al. [45] who reported a positive association between complete antipsychotic discontinuation with less-severe parkinsonism and lower incidence of health worsening compared with participants with incomplete discontinuation. Shankar et al. [65] reported no placement breakdowns or hospital admissions following antipsychotic deprescribing at 3 months follow up. This contrasts to Stevenson et al. [67] who reported 12% of participants were admitted to psychiatric assessment and treatment unit and 8% of participants required increased carer support following deprescribing of thioridazine. Two studies reported weight loss following deprescribing; Linsday et al. [56] reported the weight of 14 children returned to baseline at 12 and 24 months following discontinuing risperidone and Gerrard [38] reported a reduction in weight gain following deprescribing. Newell et al. [62,63,64] reported transient withdrawal dyskinesia in three studies monitoring participants during the reduction of typical antipsychotics.

Integrated synthesis of non randomised controlled and pre post studies

The non randomised controlled studies and pre post studies, although they have less methodological rigour, offered similar evidence to the RCTs through their use of evaluations of clinical services and longer follow up periods. In addition, the non-randomised controlled studies report more extensively on dyskinesias. One non randomised controlled study [37] and 14 pre post studies [38, 44, 46,47,48,49,50,51, 54, 55, 57, 60, 65, 66] evaluated clinical services providing deprescribing interventions, making use of a multidisciplinary model rather than the traditional medical model when reducing medication. Studies by Gerrard et al. [37, 38] and a case study by Lee et al. [75] reported that deprescribing outcomes for a range of psychotropic medicines were more successful alongside PBS compared to patients undergoing deprescribing interventions without this framework.

The external validity of the pre post studies was limited due to their lack of control or comparison group which would have improved the methodology. Well over half (67%) were conducted in inpatient settings. However, the reporting of deprescribing of psychotropic medicines other than antipsychotics allows for some tentative conclusions about the de-prescribing of psychotropics other than antipsychotics. Outcome from these studies suggest that deprescribing interventions within a multidisciplinary model may be associated with successful outcomes in terms of reducing and discontinuing psychotropic prescribing which could be maintained over a longer-term basis.

Case studies

The effects of deprescribing on several classes of psychotropic medications were reported in 13 case studies [14, 68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76, 82] (3 separate case studies were reported in one paper). Five of these studies [14, 68, 75, 76] reported an association between successful discontinuation and improved quality of life. Another set of seven studies [69,70,71,72,73,74, 82] reported a range of adverse effects including delusions, hallucinations, inappropriate sexual behaviours, transient dyskinesias, self-harm, mania, aggression and catatonia following the deprescribing intervention. Lee et al. [75] described using flexible medication reduction within a PBS framework resulting in the discontinuation of risperidone.

Comments

Post a Comment